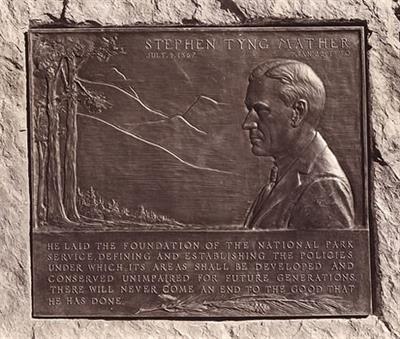

Stephen T. Mather

In the late 1800s in Death Valley, borates had just been discovered—and so had a bright, young marketing executive.

Stephen T. Mather, of 20 Mule Team® Borax brand fame, launched his career in the industry at the Pacific Coast Borax Company, which became U.S. Borax before being acquired by Rio Tinto in 1967. It was the start of a lucrative business venture, and one that would lead to his ultimate calling—helping to create the National Park Service.

Recognizing a national treasure

Under Mather’s marketing prowess, profits at Pacific Coast Borax skyrocketed. He had found his niche, and went on to make his personal fortune building and selling his own mining company.

“He built an empire in the desert, mining this material borax,” said Preston Chiaro, former CEO of US Borax and currently president of Death Valley Conservancy, which supports projects that preserve, protect and enhance Death Valley National Park. But after awhile, Mather had more than mining on his mind. The successful businessman wanted to get political about the country’s 14 national parks and 21 national monuments.

Mather pitched the  idea of creating a National Park Service to then-Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane, and in 1916 it became a reality. From 1917 to 1929, Mather served as its first director, co-running the agency with Assistant Director Horace Albright.

idea of creating a National Park Service to then-Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane, and in 1916 it became a reality. From 1917 to 1929, Mather served as its first director, co-running the agency with Assistant Director Horace Albright.

“Stephen Mather is singlehandedly the most important person behind the agency,” said Abby Wines, management assistant at Death Valley National Park, adding he couldn’t have succeeded without Albright by his side. “A lot of what the national parks are today, and the agency’s purpose, is aligned with what he set up in 1916.”

Developing the American West

Throughout his tenure, Mather emphasized the need to protect, promote and develop the parks, and encouraged private investment to attract tourists.

“The vision he had about bringing people out to the West, giving them an appreciation for the beauty of nature and connecting them to the land was extraordinary, particularly at that time,” Chiaro said. “He was a pioneer in looking at the world through the lens of sustainable development.”

In Death Valley, Pacific Coast Borax executives also recognized the need to shift focus from mining to tourism. They opened the doors of Furnace Creek Inn in 1927 while also lobbying for national park status to give the land more appeal.

However, because of Mather’s prior company connections, it was not until 1933, under Albright’s leadership, that Death Valley became a national monument. Sixty years later, U.S. Borax successfully lobbied to make it a national park, in 1994.

Mather’s influence is still felt today, and producing impressive economic gains. According to a National Park Service report, nearly one million people visited Death Valley National Park in 2013, generating more than $75 million for the community.

“Mather’s philosophy that we need visitors, or constituents, to protect the future of the National Park Service is key,” said Mike Reynolds, superintendent of Death Valley National Park. “Our mission is a balance between visitor enjoyment, and learning and preservation for the future. Without visitors, we won’t have the support we need to continue our mission of preservation. Without preservation, future visitors will not have these amazing landscapes to visit and love.”

Building on the legacy

One hundred years after the birth of the National Park Service, Rio Tinto Borates demonstrates its continued alliance with the agency through responsible land stewardship, and sustainable development and business practices. Of course, the company has a particularly strong partnership with Death Valley.

“Especially in Death Valley, we want to protect the land so future generations can enjoy it,” said Nathan Francis, land manager at Rio Tinto Borates. “When we do work there, we do our best to make it look like we were never on the property so it maintains its natural character.”

In addition to maintaining its inholdings, or privately owned land within park boundaries, Rio Tinto Borates has donated land and mineral rights, as well as archives to the park’s museum. In 2013, the company gave the mining ghost town site of Ryan, California, to the Death Valley Conservancy. Following floods in October 2015, the company also paid for repairs to 20 Mule Team Canyon Road and sponsored the creation of documentary films to highlight the park’s distinct beauty.

“Death Valley has more of a tangible mining history than any other national park,” Wines said. “Clearly, Rio Tinto values that heritage and has an interest in protecting, preserving and sharing it with others.”

Added Chiaro: “Through the company’s history, there will always be a connection back to the pioneering spirit of people who opened up the American West. We stand on the shoulders of giants.”

Resources